SUMMARY: I. Genocide. II War and Barbarity. III. Gaza: 1. Before Hamás. 2. Hamás. 3. Israel: A) Right to War (ius ad bellum). B) Law in War (ius in bello). C) Genocide. IV. Us

I. Genocide

The word genocide is relatively recent. Ninety years ago, it did not exist. It was coined by Raphael Lemkin, who included it in his book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published in 1944 and now relatively difficult to find. Here I share a digitized version of the chapter devoted to genocide.

The creation of the term was not without controversy. Philip Sands, in his book East West Street, explained it very clearly, as well as the divergences between Lemkin and his “genocide” and Hersch Lauterpacht, the Cambridge professor who put forward the concept of “crimes against humanity.” Both Lemkin and Lauterpacht were deeply aware of the context of the Second World War and the atrocities committed during it; both had influence at the Nuremberg Trials (as Sands also explains in his book), and their work continued thereafter, as we shall soon see. Yet, the existence of grave attacks against groups of people targeted precisely for belonging to a particular ethnic, national, or religious group long predated the Second World War.

During the First World War, there was what is known as the “Armenian Genocide,” in which a significant part of the Armenian population in Turkey (perhaps more than half) was exterminated. At the same time, also in Turkey, the Assyrians and the Pontic Greeks were subjected to persecutions that could be qualified as genocide, insofar as they were directed against members of certain ethnic groups precisely for being such members. There are also known cases of persecution of ethnic groups in colonial Africa that resulted in the death of a significant portion of the group’s population—for instance, the actions of Germany against the Herero and Namaqua in present-day Namibia in the early years of the 20th century. Of course, in the more distant past we can also find examples of persecutions of religious or ethnic groups aimed at their physical extermination.

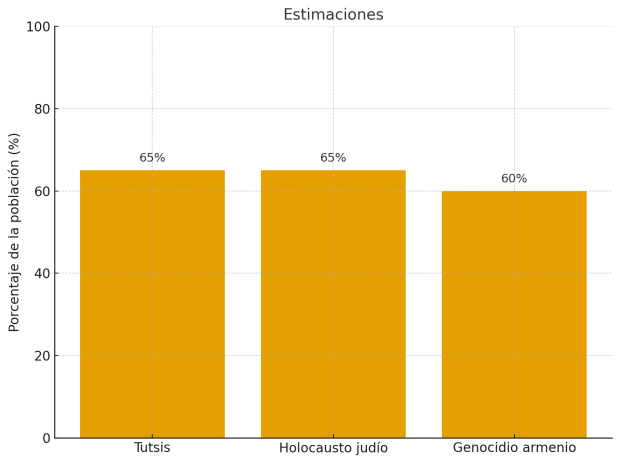

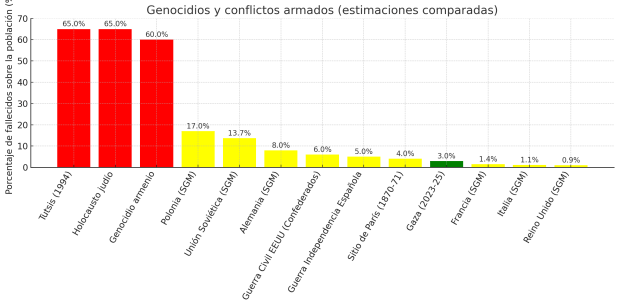

In any case, one of the most chilling aspects of genocides is that, as a rule, they entail an enormous loss of life in relation to the group that is targeted. In the case of the Armenian Genocide, as noted, at least 50% of the Armenians living in Turkey died (there is no consensus among sources regarding either the total number of victims or the size of the Armenian population in Turkey at the beginning of the 20th century). In the Jewish Holocaust during the Second World War, between 60% and 67% of Europe’s Jewish population perished. During the genocide of the Tutsis in 1994, estimates range from 50% to 80% of the entire Tutsi population in Rwanda. Harrowing.

It should come as no surprise that, despite the technical doubts raised by the concept of genocide created by Lemkin, it was embraced, because it reflected a profound and essential horror. Thus, in 1948 an international convention was concluded for the prevention and punishment of the crime of genocide. The convention provides a more limited definition of genocide than that found in Lemkin’s text. According to Article II of the 1948 Convention, two elements must be present in order to qualify as genocide: on the one hand, the commission of one of the acts listed in Article II, which we shall examine shortly. On the other hand, those acts must be carried out with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group “as such”; that is, the group itself is the target, so that the harm inflicted upon individuals is instrumental to the destruction of the group.

As for the acts that must be committed, these are:

- The killing of members of the group.

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group.

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction, in whole or in part.

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group.

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

As can be seen, the text of the Convention leaves out actions such as, for example, the confiscation of the group’s property, which Lemkin did consider a manifestation of genocide if carried out to weaken the national entities to which the victims belonged. In any case, for conduct to be classified as genocide, the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group—or part thereof—is indispensable. Proving such intent is not straightforward, since attacks or persecution against specific groups may occur for reasons other than the intention to exterminate the group.

The above helps explain why, in many cases where the existence of genocide is alleged, the lack of proof of that element of intent leads to the conduct being classified instead as crimes against humanity.

Thus, for example, it is not easy to assert that the persecution of Christians in some African countries, or other religious persecutions on the continent, can be classified as genocide, since proving that specific intent—the will to destroy a group as such—is generally not straightforward, as already noted.

II. War and Barbarity

Genocide, however, does not exhaust the catalogue of international crimes. These also include crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. Crimes against humanity encompass certain offenses committed in the context of a widespread or systematic attack against civilians; war crimes, on the other hand, generally punish actions carried out during war that lack valid military justification or that are disproportionate. In armed conflicts, it may sometimes be difficult to determine whether we are dealing with war crimes or crimes against humanity, since wars always produce civilian victims alongside combatants. In this context, crimes against humanity and war crimes serve as tools to regulate barbarity—because war is, ultimately, barbarity.

Looking at history, we see that there have been no “clean” wars (or, if there have been, they are exceedingly rare). Wars have meant massacres, torture, threats, mistreatment of prisoners, attacks on civilian populations, starvation, slavery, mutilations… One need only read The Gallic War to see this. For example, when the massacre of Avaricum is recounted:

Cum viderent in nullam partem sese dimicare audere neque ab his qui murum tuebantur locum virtuti relinqui, universi, iactis armis, signo dato ex oppido ad extremas portas concurrunt; pars a militibus impeditis in angustiis caeditur, pars equitatu circumventa interficitur. Neque ulla praedae neque captivorum petendae facultas datur: sic enim omnes sunt atrocitate recentis supplici et laboris longinqui taedio ad caedem sublati, ut ne senibus quidem, mulieribus, pueris pepercissent. Quo facto ex iis qui numero ad quadraginta milia fuerunt, vix octingenti qui primo clamore audito ex oppido eruperant, incolumes ad Vercingetorigem pervenerunt (Julio Cesar, De Bello Gallico, VII).

«When they saw that they did not dare to fight in any direction and that those who were defending the wall left no room for valor, all together, after throwing down their arms, at a given signal rushed from the town to the farthest gates. Some were cut down by the soldiers, hampered in the narrow passage, others were surrounded by the cavalry and slain. No opportunity was given to seek booty or to take prisoners: for so much were all carried away to slaughter by the cruelty of the recent punishment and the weariness of the long toil, that not even the aged, nor women, nor children were spared. As a result, of the number which had amounted to about forty thousand, scarcely eight hundred, who had burst out of the town at the first alarm, reached Vercingetorix in safety».

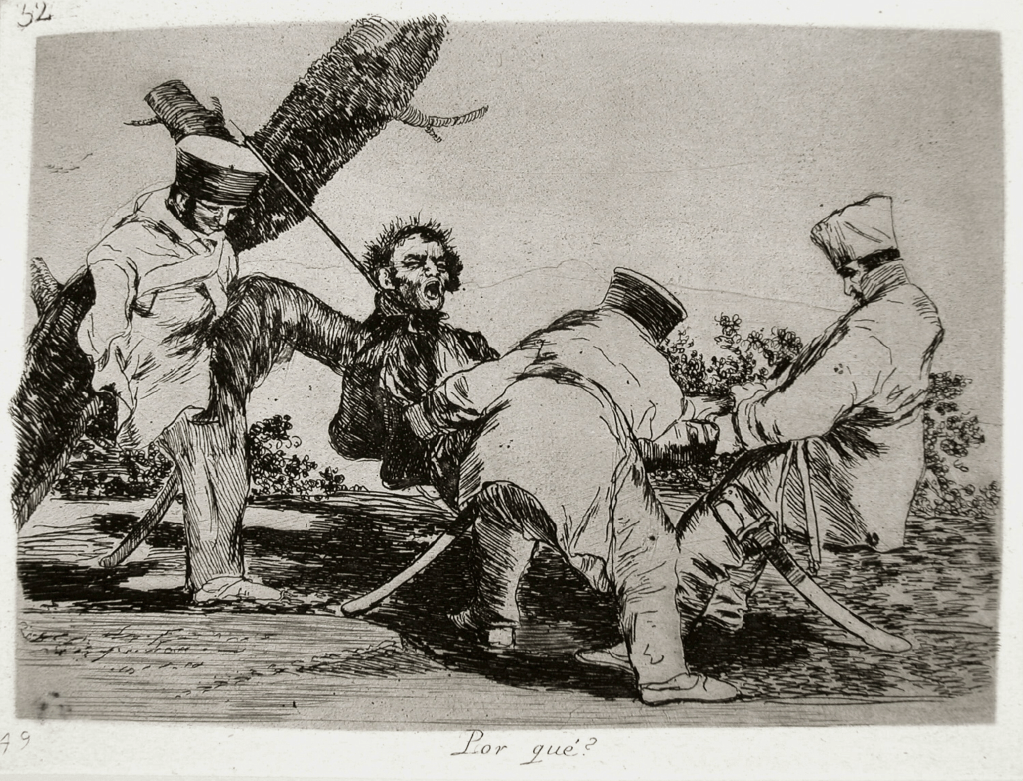

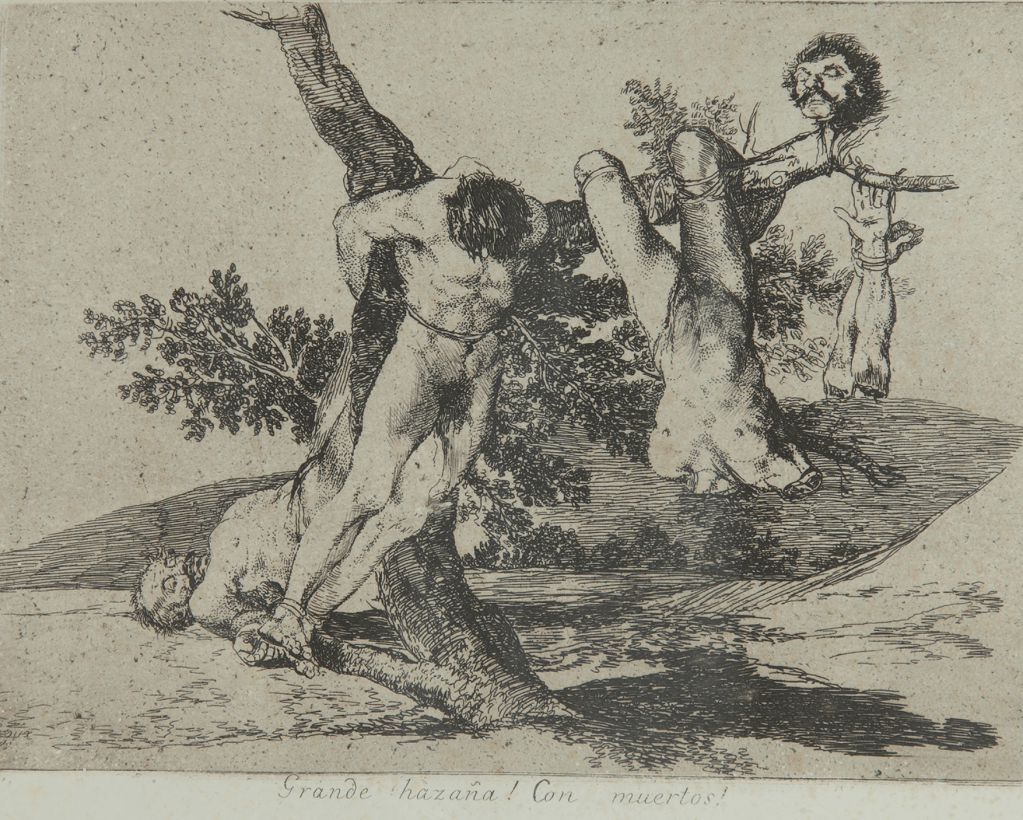

It is but one example among many. To mention just two others: on the one hand, the sack of Rome in 1527 by the troops of Charles V, where looting, rapes, killings, and other atrocities were committed against the civilian population; and on the other, Goya’s depictions of the Peninsular War at the beginning of the 19th century.

War, barbarity, and civilian victims are, therefore, terms that can hardly be separated. This explains why the dead in armed conflicts go far beyond the combatants; and not only because of the atrocities committed against the population, but also due to the consequences of military actions themselves (on June 6, 1944 alone, some 3,000 French civilians died as a result of the preparatory bombings for the Allied landing in Normandy) and the deprivations caused by the lack of food or medical resources.

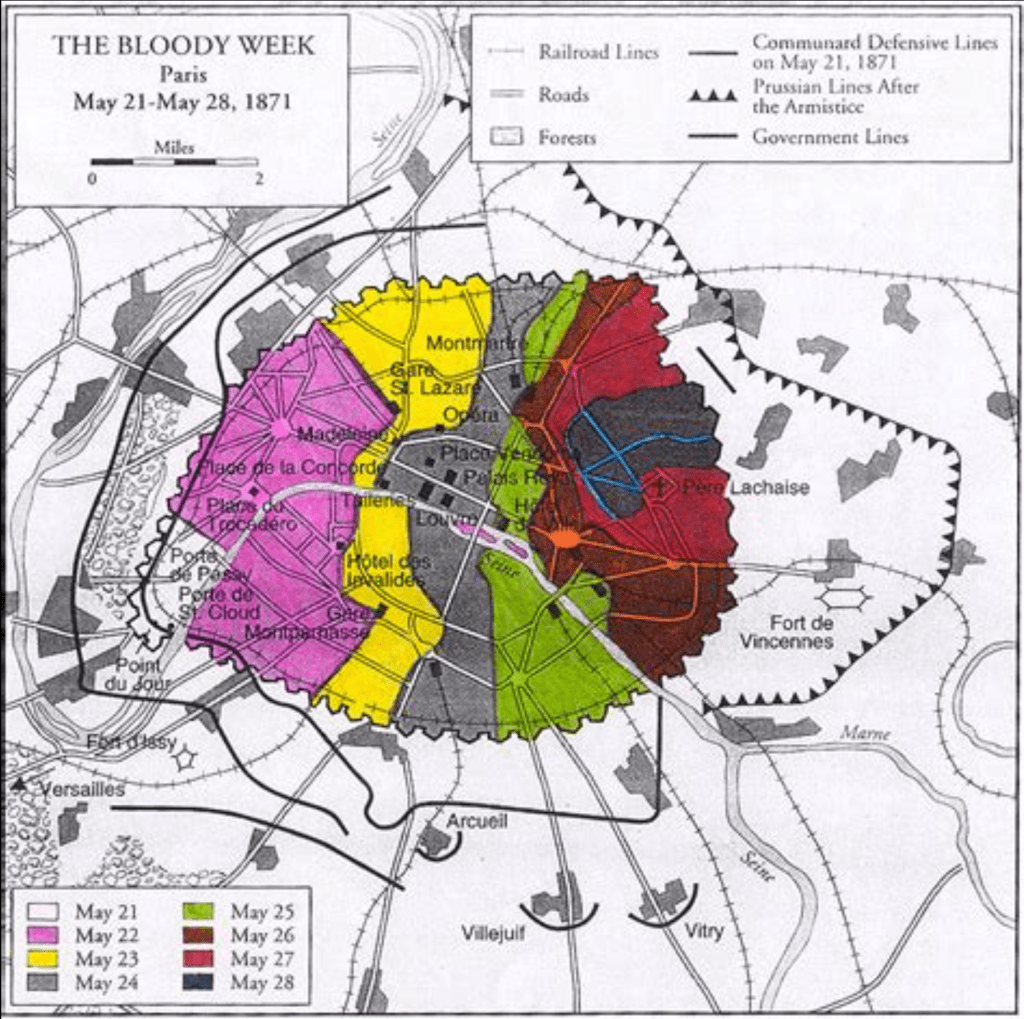

An analysis of the total victims of wars illustrates this. Thus, in the Spanish War of Independence, between 1808 and 1814, it is estimated that around 500,000 people died—approximately 5% of Spain’s population at that time. Fifty years later, the U.S. Civil War also caused about half a million deaths in the Confederacy. Considering that its population was just over nine million inhabitants, the percentage of deaths relative to the total population rose to 6%. In 1870–1871, during the siege of Paris in the Franco-Prussian War and the subsequent Commune uprising, it is estimated that nearly 4% of the city’s population perished as a consequence of the fighting and the broader effects of the conflict.

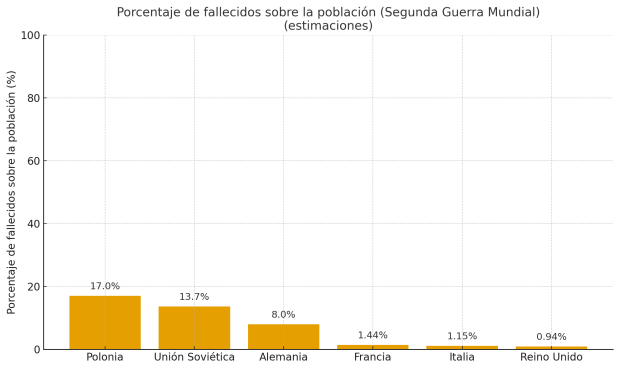

During the Second World War, the impact of the conflict on the overall population was even greater. I have already mentioned the 3,000 French civilian victims killed by Allied bombings in Normandy on a single day, June 6, 1944. That figure was probably higher than the number of German soldiers killed that same day and not far below the number of Allied soldiers who died during the landing (around 4,000).

The total death toll of the conflict confirms the extreme lethality of that war—not only among combatants but also among civilians. In Poland and France, for instance, civilian deaths outnumbered military ones. In France, there were about 200,000 combatants killed, while civilian victims numbered nearly 400,000. In Poland, the imbalance was even more extreme: around 240,000 combatants killed and more than five million civilian victims. In this case, a very large part of those victims were Jews exterminated during the Holocaust, meaning that it was the combination of genocide with the barbarity of war that explains such extraordinarily high mortality in Poland.

In the Soviet Union, too, civilian deaths exceeded military ones (around 16 million civilian victims compared with about 10 million combatants killed). In Italy, civilian and military deaths were almost equal (a little over 300,000 each), and in Germany, despite the extraordinarily high number of civilian deaths (several million), the number of combatants killed was even higher (between four and five million). Even in the case of the United Kingdom, which did not suffer the war on its own territory, there were more than 60,000 civilian victims, mainly due to the bombings of 1940 and the V-1 and V-2 rockets launched by Germany in the final phase of the war.

In any case, the percentage of deaths in those countries that endured the war on their own soil is truly harrowing.

The conflicts that followed the Second World War were also enormously lethal. Thus, for example, in the Vietnam War, between 1965 and 1973, according to the most conservative estimates, about 900,000 Vietnamese were killed, roughly half of whom were civilians—representing more than 2% of the population. In the Second Iraq War, between the start of operations in 2003 and the withdrawal of U.S. troops in 2011, there were at least 300,000 deaths, well over half of them civilians. Those 300,000 deaths amounted to roughly 1% of Iraq’s population.

The most recent conflicts are likewise terrible in terms of mortality. More than 600,000 people have died in the Syrian Civil War, which represents nearly 3% of the country’s population. Again, the percentage of civilian deaths is close to half of the total. In Yemen, a civil war has been raging for years, involving foreign actors (as in Syria), and it has caused nearly 400,000 deaths (according to the most widely cited sources, about 1% of the population), in addition to food crises and other humanitarian disasters (displacement, persecution, torture…).

The combination of armed conflict with torture, arbitrary detentions, summary executions, and other atrocities is not, as we have seen, a rarity but—unfortunately—the norm in the wars the world has known; and the existence of regulations on crimes against humanity or war crimes does not seem to have changed this reality. Examples could also be drawn from the wars in Yugoslavia in the 1990s and, more recently, from the war in Ukraine or the war in Syria.

In the case of Syria, for instance, it is striking that the country’s current president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, was once a member of Al Qaeda and Jabhat al-Nusra, and later leader of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—the latter two being fighting organizations in the Syrian war accused, for example, of carrying out public executions of women accused of adultery.

Which has not prevented the leader of that organization from addressing the United Nations General Assembly a few days ago in his capacity as President of Syria.

The message is clear: the barbarity of war may not seem so barbaric if, in the end, one emerges victorious. In fact, it is no secret that some of the actions carried out by the Allies during the Second World War might well have been judged as crimes against humanity had they lost the war. A pilot who fought in Europe with the American forces made this very remark to his superior after receiving a particular order.

According to what we have seen, atrocities in the course of wars appear to be consubstantial to them; which means that conflicts cause victims not only among combatants but also among the civilian population. These include not only deaths, but also those who suffer torture, rape, arbitrary detention, hunger, or other consequences of the conflict.

III. Gaza

1.Before Hamas

Right now we are witnessing a conflict in Gaza that is nothing more than one episode in a much broader confrontation between the State of Israel and certain countries and groups that oppose its existence. Over the decades, this confrontation has evolved; some countries that were once fierce enemies of Israel no longer maintain such an attitude toward the Jewish state, while at the same time there are now actors that did not even exist a few years ago. Moreover, among the countries and organizations opposed to Israel there are also deep divisions, which makes the situation anything but simple.

As is well known, after World War I the United Kingdom assumed control of Palestine, which at that time included present-day Jordan and the territories west of the Jordan River. Relatively soon, however, the British established separate administrations for Transjordan (today’s Jordan) and “Palestine,” the territory stretching from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean, bordering Lebanon and Syria to the north and the Sinai Peninsula to the south.

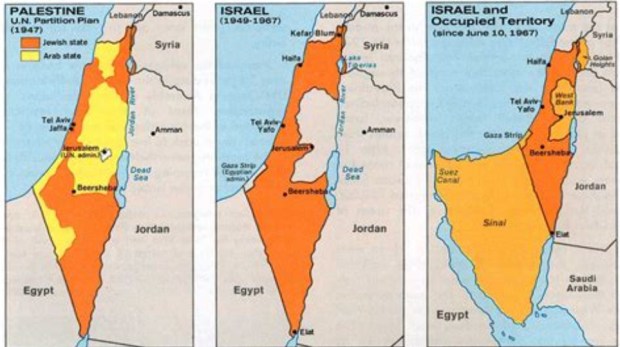

In Palestine, Jewish communities began to settle as early as the late 19th century. Some were fleeing persecution in various places (Tsarist Russia, for example), while others pursued the dream of rebuilding a Jewish nation in the land that had been their ancestral home centuries earlier. The persecution of Jews in Europe in the years leading up to and during World War II increased Jewish immigration to Palestine, which in turn provoked tensions with the Arab population already established in the territory. The British, who were responsible for the territory, proposed the partition of Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state. This solution was approved by the United Nations General Assembly on November 29, 1947.

A few months later, on May 14, 1948, coinciding with the departure of the last British troops from Palestine, the provisional government of Israel—established by the various organizations representing the Jewish population in Palestine—proclaimed the State of Israel. The Arab countries did not recognize it, and for months hostilities unfolded that ended with a ceasefire in which Israel expanded the territory originally assigned to it under the proposed partition of Palestine, and which led to the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, both during and after the armed clashes.

Israel went to war again in 1956, facing Egypt in the conflict triggered by the latter’s attempt to gain effective control of the Suez Canal (which was in the hands of a Franco-British company). Later, in 1967, during the Six-Day War, Israel came to control the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights (on the border with Syria), as well as the Gaza Strip, which had previously been under Egyptian administration.

After 1967, all of Palestine (distinct from Transjordan, present-day Jordan) came under Israeli control. The Palestinians, without a nation of their own (except for those who are Israeli citizens, approximately two million), found themselves subject to a foreign power and facing restrictions on their rights. Terrorism intensified and violence continued. There was yet another large-scale war between the Arab countries and Israel: the Yom Kippur War in 1973 (after which Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt), as well as other military operations against terrorist groups harassing Israel, such as the campaign in southern Lebanon in 1982, which aimed to destroy the infrastructure of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). During the course of that campaign, the Sabra and Shatila massacre took place, in which Lebanese militiamen allied with Israel killed several hundred Palestinian and Lebanese refugees in the camps where they were settled—camps that by the time of the attack had already become neighborhoods of Beirut.

Despite enormous difficulties, the Oslo negotiations (1993–1995) marked progress in mutual recognition between the PLO (which recognized Israel’s right to exist) and Israel (which recognized the PLO, a terrorist organization, as the representative of the Palestinian people).

This, however, did not mean the end of the conflict. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) assumed administrative functions in the occupied territories, but tensions continued as a result of the settlement policy, which involved Jewish populations being established in those territories—something rejected by the Palestinians.

he PLO abandoned terrorism and became Israel’s political partner in its new role as the civil administrator of the occupied territories; but other terrorist organizations, such as Palestinian Islamic Jihad, the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and Hamas, continued carrying out attacks—some of them suicide bombings—causing several hundred deaths. Added to this were the sustained Palestinian uprisings known as the Intifadas: the first preceded the Oslo Accords (1987–1993), and the second took place between 2000 and 2005. In the context of this second Intifada, Israel began constructing a barrier that separated certain areas of the West Bank from Israel and from some of the Jewish settlements in the occupied territories. The construction of that barrier was declared contrary to international law by the International Court of Justice.

In this context, elections were held in the occupied territories in 2006, which Hamas won. Fatah, the organization once led by Yasser Arafat and which had played a leading role for decades, lost to a group that was more violent and advocated direct confrontation with Israel. Despite its victory, Hamas did not take control of the West Bank, where the PNA under Fatah remained in power; but it did take over the governance of the Gaza Strip.

2. Hamas

Hamas was created in 1987, during the First Intifada in Palestine, and presented itself as a branch of the Muslim Brotherhood movement. Its ideology is Islamist and nationalist (Palestinian). Its 1988 Charter had a strongly anti-Israeli character, to the point that it can be interpreted as advocating not only the elimination of the State of Israel but also of the Jewish population itself (see especially Article 28). The text also refers to the role assigned to women (Articles 17 and 18) and to the notion that the practice of religions other than Islam is only conceivable “under the shadow of Islam” (Article 6). Strikingly, in the second paragraph of the Charter appears the well-known statement: “Israel will be established and will stay established until Islam nullifies it as it nullified what was before it.”

n 2017, Hamas published a new document in which, although it maintained its claim to the entire territory of Palestine (from the river to the sea, point 2), it stated that a sovereign Palestinian state with Jerusalem as its capital, within the territory defined by the 1967 borders, could represent a national consensus solution (point 20). This statement, however, did not imply renouncing the view that the rest of the territory of Palestine remained occupied territory. In addition, the document emphasized that its conflict was with Zionism, not with the Jews (point 16).

Since 2007, Hamas has controlled the Gaza Strip, having established a parallel administration to that of the PNA, which no longer exercises any function in the Strip. According to international organizations, executions—both public and private—as well as torture are carried out in Gaza. Freedom of expression and political dissent are restricted, and the role of women is secondary, in line with what was set out in Hamas’s Founding Charter (as noted earlier). The Strip also became a base for terrorist attacks against Israel, mainly through rocket launches or the construction of tunnels used to infiltrate the south of the country. However, everything changed in scale with the attacks of October 7, 2023.

n the attack, several thousand Hamas fighters likely took part, killing more than a thousand people in a single day and taking several hundred hostages to Gaza. The images of the hostages being taken into Gaza, humiliated by their captors and by parts of the population, shocked the entire world and, I assume, also Israel.

The images of what happened on October 7 are horrific; but, as I have already noted, wars are horrible, they always have been and, unfortunately, they always will be, and the existence of rules on war crimes or crimes against humanity does not change that.

And what exists between Hamas and Israel is a war; the difficulty lies in the fact that it is not an easy war to characterize legally, since one of the parties is not a state entity, but rather an organization whose goal is the creation of a Palestinian state, which does not exclude—and indeed employs—violence to try to achieve that goal, and which exercises effective control over the population and territory of Gaza, although Israel controls the borders, territorial waters, and airspace. Moreover, formally Gaza continues to be part of the occupied territories over which the PNA could exercise its administrative functions, although in fact this is not the case.

Would international law legitimize a response by Israel against Hamas, which would entail attacking Gaza with the possibility of causing harm to the civilian population? It would appear so (with the qualifications that will be examined below). It would be absurd, I believe, to argue that in the face of an attack such as that of October 7 the only legitimate legal reaction would be to request Hamas’s cooperation in handing over to Israel those responsible for the attacks and in obtaining the release of the hostages. Regardless of the legal status of Gaza, what is evident is that those responsible for both the attacks and the kidnappings are the authorities who exercise effective control over the territory and population of the Gaza Strip. We are not dealing with a terrorist organization operating clandestinely; rather, we are dealing with those who exercise public power in a territory. This is what makes the difference between a war and a police operation. That is the perspective we must adopt in order to assess Israel’s actions.

3. Israel

A) Right to War (ius ad bellum)

Thus, Israel’s operations in Gaza are acts of war. Another matter is whether there is justification from the perspective of international law, which is not as clear as it might seem, as we shall see below.

First of all, reference is often made to Israel’s right of “self-defense”; but it does not appear that Israel has formally invoked Article 51 of the United Nations Charter (the right of self-defense) as justification for its operations in Gaza. In the letter that Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General of the Organization and to the Presidency of the Security Council, it is stated that Israel “will take all necessary measures to protect its citizens and defend its sovereignty against the ongoing terrorist attacks perpetrated by Hamas and other terrorist organizations originating from the Gaza Strip”; but it does not explicitly invoke the right of self-defense.

And there are reasons for this. The right of self-defense is conceived for aggressions by one State against another State, and the actions it legitimizes are limited not only by the principle of proportionality but also by that of necessity; that is, only those measures aimed at neutralizing the aggressor’s attack capabilities are justified. Moreover, the seriousness of the attack must be assessed in “international” terms. In other words: is Israel’s existence threatened by Hamas’s attacks? Is its territorial integrity at risk? It does not seem so. Of course, this does not mean that Israel can do nothing; but from the strict perspective of the right of self-defense as regulated in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter, I am not convinced that one could justify an operation aimed at taking control of Gaza. Consider, for example, if Ukraine were to claim—if it had the capacity to do so—that the exercise of its right of self-defense against Russian aggression entitled it to occupy the whole of Russia. In fact, there has already been debate as to whether that right of self-defense justified its attack in Kursk, which led it to control part of Russian territory for a time.

Too little attention is paid to how limited the right to use force is, even in cases of self-defense, after the United Nations Charter. If the current doctrine on the use of force between States had been applied in 1945, the Allies should have stopped their advance on Germany at the Rhine River, and the Soviets would not have been able to go beyond East Prussia; or they would only have been allowed to penetrate Germany as far as necessary to neutralize its military capability. The United States would not have been able to invade Okinawa and, later, occupy Japan. Unconditional surrender is not a legitimate objective for the use of force.

And yet, in the face of an attack such as that of October 7, and with more than 200 hostages in Gaza, one must ask whether it is reasonable to expect a State to limit itself to requesting that the Security Council condemn such attacks. On the other hand, in this case we are not dealing with aggression by another State, nor even from the territory of another State, since Gaza is neither another State nor part of Egypt or of any other internationally recognized country—except for Palestine itself, but together with the West Bank, not as an autonomous entity. Moreover, Israel has never relinquished control of Gaza’s land borders, airspace, and territorial waters; therefore, in a certain sense, it continues to be the “occupying power” of the territory. From this perspective, and with qualifications, Israel’s position vis-à-vis Hamas would be similar to that of any State facing an armed group that manages to control part of its territory. In such cases, the use of force to regain effective control of the territory would indeed be justified, which would entitle Israel to an operation aimed at achieving total control of the Strip; with the caveat, however, that the Gaza Strip is not territory of the State of Israel, but rather, in its case, occupied by Israel. That said, Israel does not emphasize this argument, because doing so would imply that it must assume responsibility over the territory; something that, nevertheless, it now curiously seems willing to do.

B) Law in War (ius in bello)

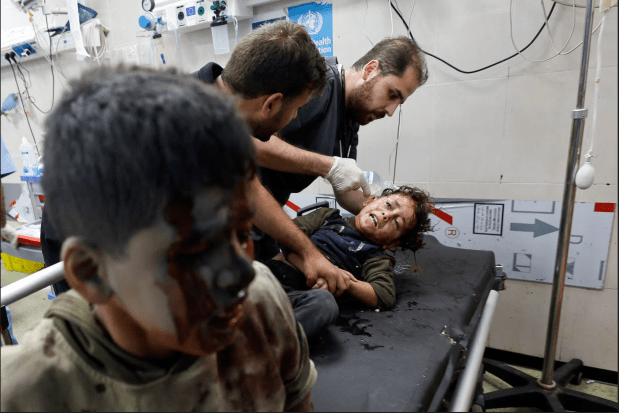

Thus, doubts can be raised about the legal fit of Israel’s military operations in Gaza; but, broadly speaking, there has been less discussion of that than of the conformity, with international law, of the way those operations are carried out. In other words, whatever the justification or argument used regarding Israeli actions, from an international perspective they must be actions directed against military objectives and that cause the civilian population the least possible harm. If these requirements are not met, we could be facing war crimes or crimes against humanity. In the almost two years we have been in this phase of the conflict (because the conflict, in reality, as we have seen, began much earlier), accusations of excesses by the IDF (Israel Defence Forces) have been frequent. Moreover, the images of bombed hospitals, displaced civilians and civilian deaths, including children, have impacted world public opinion.

The previous images are apparently genuine; others that have been circulated, however, have been proven to be false or are likely false, even generated with AI tools.

In war, controlling the narrative also matters; this is why each side will try to draw international sympathies to its cause, and it is natural to attempt to portray the adversary as bloodthirsty and oneself as a victim. Israel disseminated in various ways the images of the October 7 attacks, and since the beginning of the offensive in Gaza the consequences of Israel’s military actions have been widely circulated, with emphasis placed on the targeting of civilian objectives such as hospitals, journalists, or people waiting for food deliveries.

It is not only a matter of appealing to public opinion emotionally, but also of moving into the sphere of legal assessment, so that there are already cases before the International Criminal Court against the Prime Minister of Israel and his Minister of Defense for actions in Gaza. They are accused of crimes against humanity and war crimes.

What is being investigated is whether Israel’s actions are directed against civilians as part of a widespread and systematic attack on the civilian population in Gaza. If this were the case, it would constitute crimes against humanity.

From the Israeli perspective, however, the argument put forward is that, despite efforts made to minimize harm to the civilian population, the operation to dismantle Hamas—given the organization’s penetration into the territory and among the population—makes it impossible to carry it out without civilian casualties.

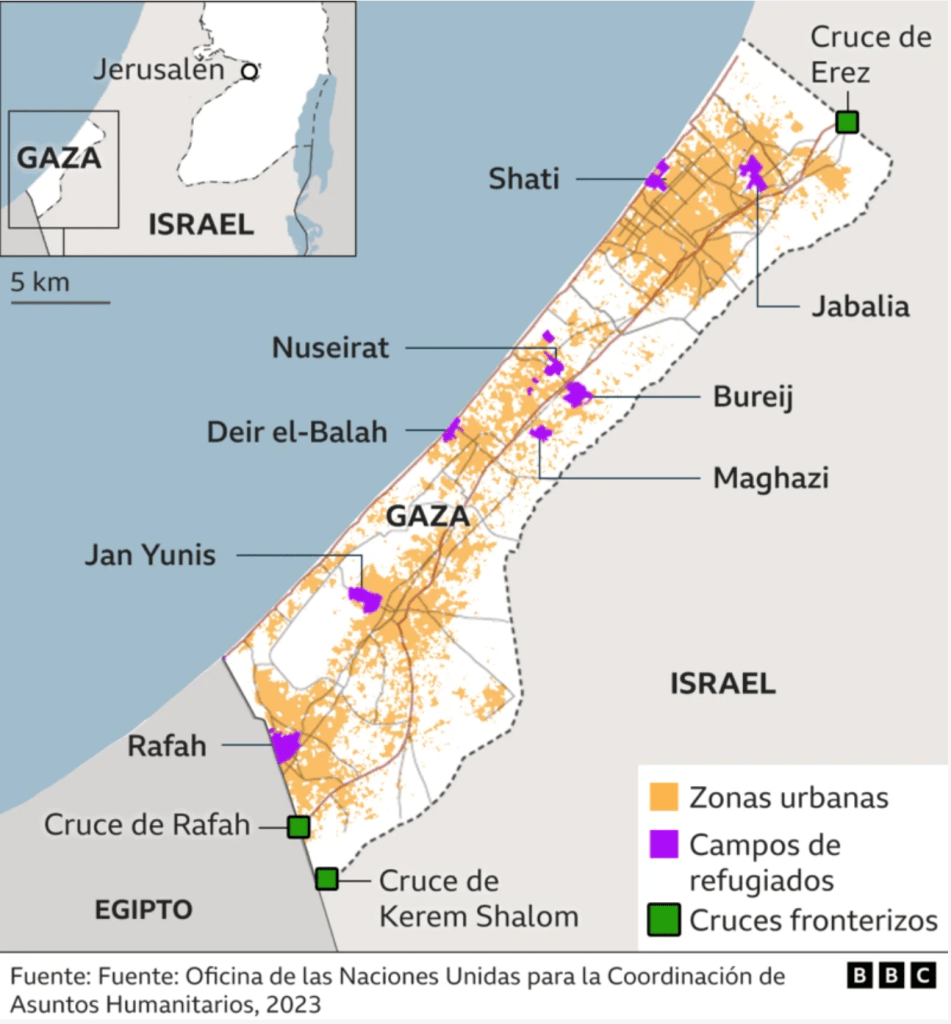

Of course, it will surely be difficult to carry out a large-scale military operation in a territory with a population density of more than 6,000 inhabitants per square kilometer without the number of civilian casualties being high. To get an idea: the Gaza Strip has a surface area similar to that of the Maresme region in Barcelona, but with five times the population.

Naturally, the immediate question is why the population of Gaza does not flee. There is a border with Egypt (the Rafah crossing) that would allow an exit for civilians, or at least for part of the civilian population (children, the elderly, women), as happened in Ukraine after the Russian invasion, or as we have seen in so many conflicts (such as Spanish Republican refugees who crossed into France in 1939). The problem here is that Egypt does not allow this flow of refugees, which leaves the population of Gaza trapped. Israel, before carrying out operations in a given area, warns the population to evacuate; but where are they to go? It is a situation similar to a siege, but one in which there is an escape door that is not used. In fact, considering the besieged area and the population affected, the war in Gaza resembles the siege of Paris in the years 1870–1871 that has already been mentioned, even in terms of the order of magnitude of the deaths. The siege of Paris is estimated to have cost the lives of 4% of the population, and so far in Gaza it is estimated that 2.5% of its population has died.

In addition to the high population density, there is another factor that makes operations more difficult: the fighters do not wear uniforms. From the perspective of international humanitarian law, this requires the duty of distinction to be applied with the utmost rigor in order to avoid civilian casualties, but it is not a negligible factor when legally assessing the actions of the IDF in Gaza.

With regard to the attacks on hospitals, mosques, and other civilian buildings, Israel’s argument is that they are used as weapons depots or infrastructure by Hamas, which does not distinguish between military and civilian facilities, or even exploits Israel’s obligation to respect the latter for military purposes. The evidence presented by Israel has been questioned, insofar as independent verification is limited or non-existent, and also because—even admitting the military use of certain civilian facilities—it could still be debated whether the Israeli attacks are proportionate. Moreover, it has been argued that some of those attacks (for example, on the Al-Ahli hospital in October 2023) were in fact the result of failed Hamas rockets aimed at Israel.

In short, it is obvious that Israel’s operations in Gaza have caused numerous civilian casualties. Unfortunately, this was to be expected in a war taking place in such a densely populated area, where fighters tend to blend in with the civilian population and where those controlling hospitals, schools, and infrastructure are the same ones doing the fighting. However, this difficulty does not exempt Israel from responsibility, since the obligation to apply the principle of distinction and proportionality with the utmost rigor in such cases is beyond dispute.

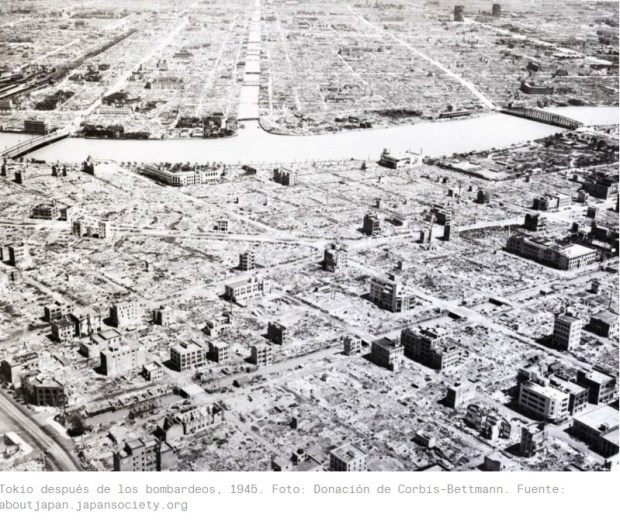

The fact that what is happening in Gaza corresponds point by point with what is common in all conflicts—especially those fought in urban centers—does not alter the legal characterization that Israel’s actions may merit. Nothing we are witnessing is different from what the Allies did during World War II; but, as we noted earlier, under today’s rules the Allies would not have been able to move beyond Germany’s borders in 1939 nor demand its unconditional surrender. If the bombings of Dresden or Tokyo were to be filtered through the lens of current humanitarian law, many people who today have streets named after them, pictures in institutions, or even Nobel Prizes should be standing trial before the ICC.

(Dresden in 1910)

(Dresden after the bombing of 1945)

Thus, the legal assessment of Israel’s actions cannot rest on comparisons with the past. The fact that today, as we have seen, it is common for armed conflicts (international or civil) to be accompanied by acts that must objectively be classified as war crimes or crimes against humanity, and that are not prosecuted (see supra section II), does not affect the characterization of Israel’s actions either. What must be examined is whether civilian casualties could have been avoided and whether all necessary diligence was exercised to that end; this requires an individualized analysis of each action, an examination that, at this point, is difficult to carry out objectively.

Another issue that must be considered is that of humanitarian aid, including food aid, in Gaza. One of the accusations against Israel is that it prevents the delivery of such humanitarian aid; however, Israel argues that the international agencies distributing that aid are not neutral, that in some of them there are workers who have collaborated with Hamas, and that instead of being distributed neutrally among the entire population according to their needs, the aid is used to assist Hamas or to strengthen Hamas’s role among the population (by indirectly controlling the delivery of aid). For this reason, Israel has proposed that the aid be delivered by Israel itself, a proposal that has been rejected by the UN and other international agencies.

The problem has a certain complexity. Israel controls access to Gaza and, in addition, controls part of the territory, although another part remains under Hamas control. The distribution of humanitarian aid should be carried out by neutral actors, but Israel denies that, for example, UNRWA (the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) acts as a neutral agent. Thus, for instance, while UNRWA refuses to cooperate with Israel in the delivery of humanitarian aid, it does not raise the same issue with Hamas when delivering aid in the areas still under that organization’s control. Since it does not consider UNRWA a neutral agent, Israel claims its right, as the power that de facto controls the territory, to inspect the aid and verify that it is not intended to benefit the fighters.

On the other hand, Israel offers “safe” zones within the Strip itself to receive humanitarian aid; but Hamas discourages the population from making use of this possibility, as reported by several sources, including the Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel of June 14, 2024 (no. 59, in fine).

That is to say, the problems of lack of humanitarian aid in Gaza do not have a direct and obvious answer such as: “Israel wants to starve Gazans”; rather, they involve responsibilities on the part of several actors, including Hamas and also the humanitarian agencies that have not been able to present themselves as neutral agents in the conflict.

From what we have seen so far, the ICC has already begun to act with regard to the Israeli authorities for the possible commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Obviously, these are accusations that are not entirely without basis, given current international humanitarian law; but they must be examined carefully in light of the circumstances of an armed conflict taking place in a fundamentally urban, densely populated environment, in which one of the combatants is at the same time the party controlling hospitals, schools, mosques, and, until the beginning of the Israeli operation, the only de facto public authority on the ground. This is compounded by the tendency to blur the line between civilians and combatants who are not part of a uniformed and formally organized army.

C) Genocide

Despite all of the above, the debate—especially in some countries, and we will have to return to this a little later—focuses on whether or not Israel is committing acts of genocide in Gaza. South Africa filed a case against Israel before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to this effect, which resulted in a ruling by the Court in January 2024. While it did not affirm that genocide was being committed, it did consider South Africa’s allegations to be plausible and adopted provisional measures.

Apart from these provisional measures (and others that followed along the same lines), which do not qualify Israel’s actions as genocide, there are no resolutions by either the UN Security Council or the UN General Assembly that characterize Israel’s actions in Gaza as genocide. There is, however, a report by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel (COI-OPT), which we will address shortly, as well as numerous statements by political leaders around the world, artists, organizations, and ordinary commentators who do not hesitate to describe what is happening in Gaza as genocide.

On this issue, the only thing I am certain of is that it is not possible to be certain. I will say in advance that my impression is that genocide is not being committed in Gaza, and I will give my reasons; but always with the caution that what is happening on the ground is not sufficiently known, and that in situations of conflict it is difficult to know the reality of what is taking place because propaganda comes from all sides involved. Only in the future, with more data and testimonies available, could a balanced judgment be made.

As I have just indicated, however, my impression is that what is happening in Gaza cannot be qualified as genocide. As I mentioned in Section I, proving the crime of genocide is difficult, because it requires establishing an animus, the intent to destroy all or part of an ethnic, national, or religious group, which is not easy. Moreover, since genocide is regarded as the most heinous of crimes, the standard of proof must be even more compelling; that is, there can be no doubt about genocide—or, better put, if there is doubt, then it is not genocide.

By this I do not mean that the doubts we have now invalidate the accusation of genocide; what I mean is that once all the evidence is available, it must be clear that there was a will to exterminate all or part of a particular group, as such (we emphasized the importance of that “as such” in Section I); if that clarity is absent, the classification should be different.

But before addressing that animus, I want to pause on another point: although it may seem cold or dehumanizing, the question of numbers is not entirely irrelevant; and if we consider the death toll in Gaza, we see that it is closer to that of an armed conflict than to that of a genocide.

Of course, the above is not definitive. Genocide can exist where there is a clear will to extinguish an ethnic, national, or religious group, even if—fortunately—that purpose does not succeed; but if we want to be objective, when the percentage of victims resembles so closely that of a military conflict, it is necessary to explain the reasons why the alleged perpetrator of genocide fails to carry out his purpose.

In the case of Gaza, where there are military explanations for the actions, the burden of proof rests on those who claim that these military operations are in fact concealing a genocidal intent, which, in my view, fits poorly, for example, with the prior warnings issued by the IDF before bombings or attacks. The existence of such warnings does not make the actions legitimate, and it cannot be ruled out that they may be considered war crimes or crimes against humanity, as we noted earlier; but it does make it more difficult for them to be considered genocidal acts.

The COI-OPT report, however, takes this step—although, in my view, without being convincing.

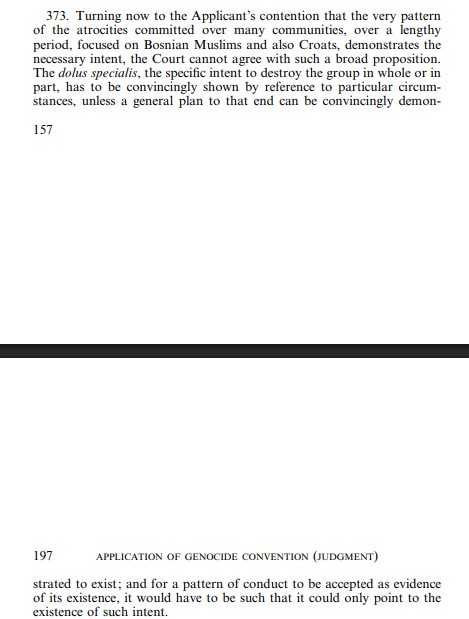

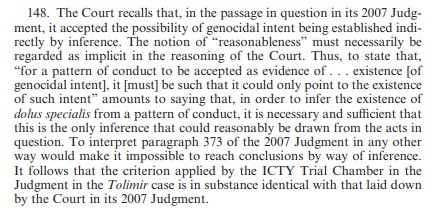

When it comes to proving genocidal intent, inferences that allow for another interpretation are not sufficient; the only reasonable conclusion must be the purpose of exterminating an ethnic, national, or religious group “as such.”

(ICJ Judgment of 26 February 2007 in the case Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro)

(ICJ Judgment of 3 February 2015, Croatia v. Serbia)

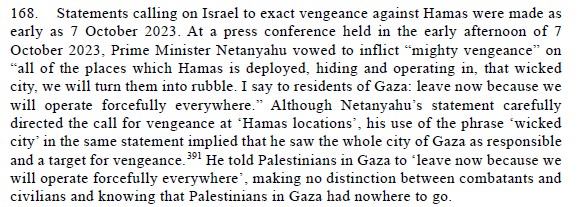

In the COI-OPT report, however, the approach is the opposite: in statements that could be interpreted as excluding genocidal intent, emphasis is placed instead on those aspects that would lead to the conclusion that such a will to exterminate does exist. For example, in paragraph 168 of the Report it is noted that, although Netanyahu explicitly addresses Hamas, it is considered to show genocidal intent that he uses the expression “wicked city.”

In paragraph 169, for its part, genocidal intent is inferred from statements by Israel’s Minister of Defense that explicitly refer to Hamas; although, read in their entirety, they could be interpreted as referring only to the combatants and not to all Palestinians.

In this regard, the COI-OPT considers relevant statements by President Herzog that did not explicitly call for genocide and that were later qualified; that is, a pattern of conduct can be observed on the part of the Commission consisting in emphasizing those statements that may support genocidal intent and downplaying those that contradict it, which is precisely the opposite of what should be done in such cases.

In conclusion, the COI-OPT document appears to show a certain confirmation bias toward the thesis of genocide, which does not seem consistent with the regulation of this international crime or with the interpretation given by the International Court of Justice.

As we saw in the previous section, Israel’s actions in Gaza—setting aside their ultimate justification (ius ad bellum)—could amount to war crimes or crimes against humanity, even though they do not depart from what have—unfortunately—been common practices in past wars and even in present ones (the war in Syria, to name just one example). However, attempting to go further and qualify them as genocide, I believe, does not withstand objective analysis. The crime of genocide, precisely because of its gravity, because of the examples we have had of it, because of the millions of victims it has claimed, and because of the role played in the international order by the mechanisms for its prevention, prosecution, and punishment, must be used with rigor and must not be instrumentalized.

IV. Us

The war in Gaza is not something distant from us. At the same time, it is profoundly divisive in Western societies, including Spanish society.

Being fully aware of the complexity of the Middle East conflict, when the attacks of October 7, 2023 took place I was deeply affected. These, moreover, are not feelings one chooses; but the truth is that, although there are other examples of massacres and atrocities, this one struck me deeply.

In the state of mind I was in on October 7 and 8, I was surprised by the calls for pro-Palestinian demonstrations on those days. Indeed, Palestinians are one thing and Hamas is another, but at that moment such demonstrations—which, as was later confirmed, were anticipatory reactions to Israel’s response—could be understood as support, even if indirect, for the massacre perpetrated by Hamas.

These demonstrations also coincided with statements by politicians and authorities which, in that context, could be interpreted as support for the Palestinian claims that had led to the October 7 attacks.

In those days I could not stop thinking that those demonstrations and statements would not have taken place had the October 7 attacks not occurred. The idea that there was a connection between those atrocities, demonstrations in Madrid or Barcelona, and statements by leaders of my own country sent a chill through me.

And let me be clear: I am aware, as I have said, that in the Middle East conflict Israel, or those who support (or are supported by) Israel, have committed many atrocities; but just as I would have found it nauseating to see a pro-Israeli demonstration immediately after the Sabra and Shatila massacre mentioned in Section III.1, I was repulsed by the pro-Palestinian demonstrations after the October 7 attacks.

Since October 2023, as the images of October 7 have faded and the actions of the Israeli army have come to the forefront, condemnation of Israel has grown in many countries; and in some, such as ours, the Palestinian cause has become an instrument of polarization. The insistence on demanding that Israel’s actions be labeled genocide—even though, as I explained in Section III.3.C), the only clear thing is that it is not clear—is, in my view, indicative of this instrumental use of the Gaza conflict. In Spain, for example, faced with almost any criticism the opposition raises against the government, the argument is that the PP must call the situation in Gaza genocide.

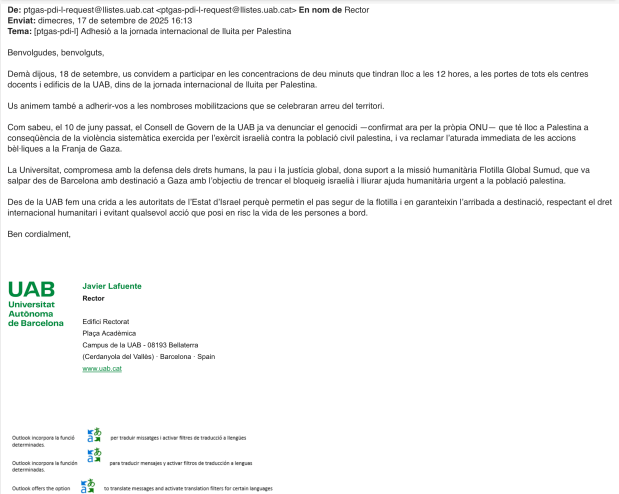

An insistence on the use of the term “genocide” that has penetrated many institutions. Thus, for example, a few days ago, at my university, the Autonomous University of Barcelona, we received the following collective email from our Rector:

As can be seen, he states that the UN has confirmed genocide in Gaza, which is quite far from the truth, since he is referring to the COI-OPT report, which, as its very name indicates, is independent; that is, it does not express the position of the UN as an international organization. Moreover, he refers to an earlier statement in which he had already addressed the university community, asserting in advance that what is happening in Gaza constitutes genocide.

From my perspective, this kind of institutional stance on an issue of such difficulty (as we have seen) contributes neither to a calm debate nor to a better understanding of the problems at stake. As I have said, I am outraged by the instrumentalization of the conflict, an instrumentalization that, as I have already suggested, seems intended to deepen the division of society rather than to help address the many problems we face, both in our own country and elsewhere.

Beyond this instrumentalization, there is another dimension that must be considered. With all the complexity of the Middle East conflict, it is still possible to identify its sides. To simplify greatly: on one side, Israel; on the other, the Palestinians. In Spain there are those who unreservedly adhere to the Palestinian cause—they are “their own,” and they defend Palestinian advances as if they were their own and lament any setbacks as if they were personal. The demonstrations that followed immediately after the October 7, 2023 attacks, to which I referred earlier, cannot be explained without this “they are our side” component.

I do not identify with either side. I do not hide the fact that, as I said, the October 7 attacks had a deep impact on me, nor do I hide my sympathy with the Jewish people, especially in light of what they have suffered in the past century and of the ties they have with my own country, Spain. That said, this does not prevent me from recognizing their abuses and mistakes. I have always criticized the settlement policy, the construction of the barrier, and, moreover, I disagree with the conception of Israel as a state based on a particular religion (or ethnicity). I believe that countries should be built on citizenship, not religion, and on radical equality among all people—something which, in my view, is not the case in Israel.

Still less could I ever identify with Hamas. It is enough to read its founding documents to realize that its outlook is Islamist, in the sense that in the state it seeks Islam would stand above all other religions. It does not regard women as equal to men, and it carries out violence against civilians without even asking whether they are combatants or not. I would be repulsed to do anything that could be understood as support for Hamas.

And yet, from my own country, from my own city, a flotilla sets out in which a group of people head toward Gaza in an attempt to break the Israeli blockade and in explicit support of the Palestinian cause.

The discourse of the two sides is that one must stand with one of them. It is significant that at the time of the flotilla’s departure Ada Colau said that if Gaza does not surrender, neither could they surrender.

It is significant because the ones who can (or cannot) surrender are those who are fighting; and in this war, the ones fighting are Israel and Hamas. Gaza is the battlefield. Thus, Colau’s statement can only be understood to mean that if Hamas does not surrender, neither will they.

Who knows if in the future we will see Netanyahu in prison and one of Hamas’s leaders speaking before the United Nations General Assembly, just as Ahamda Al-Sharaa—now President of Syria and not so long ago the leader of an organization that practiced summary executions, torture, and arbitrary detentions—did a few days ago. If that happens, I believe it would not be good news. If you do not treat all criminals equally, in the end no one will believe in justice, and it will be assumed that the only things that matter are force and propaganda.

It is not the world I would like, but, unfortunately, in the world closest to me it is dramatic to see how concern for rigor and objectivity has been replaced by the instrumentalization of others’ suffering, the pursuit of polarization, and the subordination of institutions—which should be neutral and foster open debate—to propaganda.

2 comentarios