When we were immersed in the procés, Félix Ovejero often repeated an idea that is worth keeping in mind: democracy and solidarity operate—if they operate at all—within relations inside a given political community. International life is not governed by those principles, but rather by those of international law (with luck, one might add) and by the rule of defending one’s own interests, if necessary by force.

What is happening in Venezuela is a perfect example of all this. We could go as far back as we like, but I think it is enough to start in July 2024.

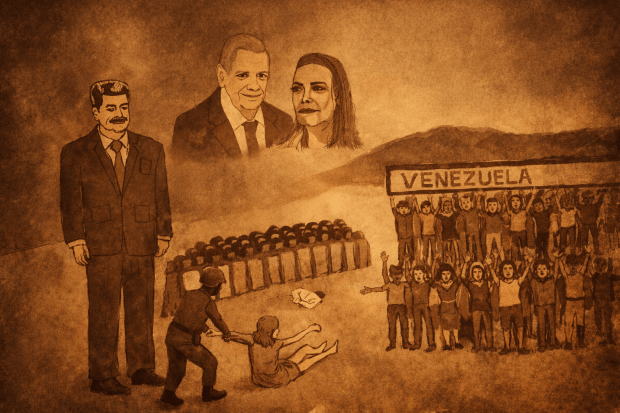

There were elections in Venezuela, and the opposition, in an operation that in my view deserves the highest praise, managed to show the world that they were the ones who had won and that Maduro had lost.

Perfect—very good. And from there, what?

Because the state is nothing more than the monopoly of force, so no matter how right you may be, if the one who holds the force wants to retain power, he will retain it, as indeed happened.

Maduro was an illegitimate president, yes; but he was the one who controlled the country—the armed forces, the police, the postal service, and the borders. Therefore, from the perspective of international law, he was the president and enjoyed, for example, immunity from jurisdiction.

In the same way, states are (in principle) barred from intervening in the internal affairs of another state; this applies even when the government is tyrannical, illegitimate, or commits crimes against its own population. International law does provide mechanisms to act in such situations, both from the standpoint of international criminal law and, in some cases, even by authorizing military operations; but outside those circumstances, any military intervention in another country constitutes an internationally wrongful act.

From the opposition’s perspective, Trump’s intervention could initially be seen as positive, insofar as it might have led to the overthrow of Chavismo. But reality, as we have seen, is quite different. The United States is not intervening to restore sovereignty to the Venezuelans, but rather to control the country, playing the role of arbiter that grants or withdraws legitimacy from both sides of the conflict (Chavismo and the opposition).

If Trump’s operation lacked a legal basis from the outset, it now also lacks any kind of legitimacy that might have been attributed to it when it was perceived as support for the actual results of the 2024 elections (after all, the United States recognized Edmundo González as the legitimate president).

The lesson is a harsh one. Venezuela suffered under the Chavista regime and will continue to suffer it; but now it does so under the tutelage of the United States, which does not even bother to conceal its attempt to control the country, now turned de facto into a semi-protectorate.

In this context, one can probably understand the maneuver to remove Corina Machado from the country, so that the U.S. government can now claim that the opposition has left Venezuela. The opposition “does not cause trouble.”

I don’t know—it is enough to feel desolate. I am not Venezuelan, but it is difficult not to identify with Venezuelans who have suddenly seen their capacity to decide their own future disappear. The theft of the elections, followed by the opposition’s inability to articulate a movement that posed even a minimal threat to Chavismo, has ended in the loss of the country for both sides.

I hope that others—especially in Europe (I will return to this at the end)—are able to grasp the consequences of all this.

And a word about international law.

These days it is often said that international law “does not exist.” That is not true. A large part of international law continues to be applied every single day, from diplomatic relations to the law of treaties, as well as the regime of borders, the law of the sea, and the legal framework governing areas not subject to state sovereignty. International law is more than wars.

That said, it must be acknowledged that the principles of non-use of force, non-intervention in the internal affairs of other states, and respect for territorial integrity are seriously damaged.

And the United Nations are also very seriously damaged.

Two of the permanent members of the Security Council are engaging in activities that are clearly prohibited by international law. From that point on, what legitimacy does the United Nations Security Council retain? None. And the United Nations without the Security Council—what are they? An empty shell, something akin to a university assembly that has moreover, on more than a few occasions, fallen into questionable biases (I have in mind certain statements by some of its committees precisely in connection with the procés, with which I began, and the September document on Gaza is, as I tried to explain a few months ago, deplorable.

In short, the rules established after the Second World War regarding the use of force have become obsolete. It is true that perhaps they were misguided from the very beginning. As I also recalled a few months ago, under contemporary international law it would have been very difficult to justify the Normandy landings, and the Allied troops would certainly not have been able to enter German territory at the end of the Second World War.

There is work to be done for international lawyers. They must stop merely repeating, “this is contrary to international law,” and start thinking about real international law. We should return to Kelsen’s old lesson: one can explain a legal order independently of its effectiveness, but if that order ceases to be applied, it no longer makes sense to qualify it as legal.

And it would be desirable for the EU to be productive along these lines. In the twenty-first century, the EU is somewhat like the Netherlands in the seventeenth century. It was not the great power of the time (in the seventeenth century those were Spain, France, and to a lesser extent England—also Sweden); but it did possess real military capacity, commercial strength, and inventiveness. And it was in Holland—pardon, in the Netherlands—that the foundations of modern international law were laid, the law that ultimately led to the Peace of Westphalia.

Today’s Spains, Frances, and Englands are the United States, Russia, and China. The EU—if it earns respect, revitalizes its economy, and believes in itself—may still have something to say; but to do so it must stop repeating mantras from the past, see the world as it really is, and understand that nothing is guaranteed, that nothing will be given to it for free, and that it must live each day facing a new threat—one that may come from Russia, from China… or from the United States.